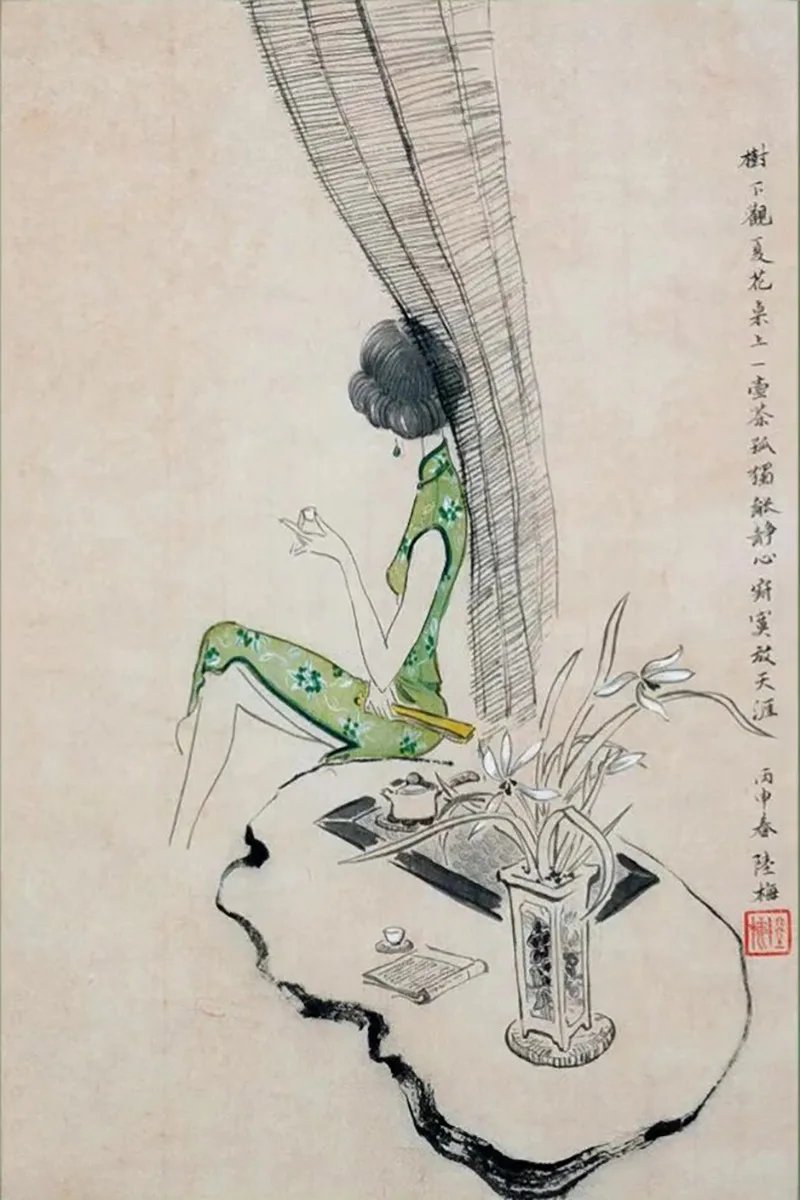

1970s Chinese Qipao

From the 1950s to the 1970s, while the qipao faded in popularity across both sides of the strait, Hong Kong, China stood out as a rare blossom, where women like Maggie Cheung brought to life a uniquely Hong Kong style and charm.

From the post–World War II years to the 1970s, Hong Kong was truly a world of qipaos. Most women from the working and professional classes wore qipaos to the office. My mother was an elementary school teacher, and every morning she would leave home early, dressed in one of her qipaos. It was the most local of garments—and the most authentically Chinese attire.

In Cantonese, the qipao is often called a cheongsam. A woman walking gracefully in a long cheongsam carried with her a distinctive feminine charm that embodied both Hong Kong’s character and the refined elegance of Chinese culture. In fact, many secondary schools in Hong Kong adopted the qipao as part of their girls’ uniforms. Even today, several schools still preserve this tradition, including Pui Tao Secondary School, True Light Middle School, St. Paul’s Co-educational College, St. Stephen’s Girls’ College (summer uniform), Ying Wa Girls’ School, Heep Yunn School, Maryknoll Fathers’ School, Fanling Kau Yan College, Hong Kong Teachers’ Association Lee Heng Kwei Secondary School, and S.K.H. Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School.

Perhaps this is something uniquely Hong Kong. No other city has so many schools where the uniform for girls is the qipao. Though the materials used are simple and practical, these uniforms carry the same understated elegance once favored by female students at Peking University in the early Republic of China—graceful in their simplicity, fashionable yet scholarly in spirit.

From a broader historical perspective, Hong Kong between the 1950s and 1970s was the city with the highest “qipao density” in the world. At that time, mainland China was swept up in waves of political movements, and the qipao was considered “politically incorrect.” In Taiwan, it was mostly worn within mainlander circles, so the number of women wearing it was relatively small. Hong Kong, however, continued the traditions that had flowed from Guangzhou and the rest of China since the late Qing and early Republican eras. The qipao became a cultural trend — the most local and, at the same time, the most authentically Chinese garment.

I still remember going with my mother to Ping On Mansion in Yau Ma Tei to have her qipao made by a Shanghainese tailor. I was just a primary school student then, watching from below as the tailor carefully took her measurements, calling out the numbers in Shanghainese while his wife swiftly jotted them down. My mother, a schoolteacher, wore simple, modestly colored qipaos to work every day, but she also had a few more fashionable and elegant ones specially made as her “dining dresses,” reserved for weddings or important banquets.

Later, when my older sister graduated from university and followed in our mother’s footsteps to become a teacher, she too wore qipaos to school. The qipao, it seemed, had become a kind of “coming-of-age uniform” for women of that generation. Regardless of color or design, each flowing cheongsam embodied a woman’s graceful maturity and quiet elegance.

Later, when I watched Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and saw Maggie Cheung exude such grace and allure in her qipaos, I couldn’t help but think of my mother’s era — a time when the women of Hong Kong wore the qipao as a quiet yet powerful expression of modern Chinese elegance. From schoolgirls to teachers, from office ladies in Central to professionals across the city, the qipao was not just attire; it was Hong Kong’s cultural signature — the most distinctive symbol of its local charm.

Many old Hongkongers still remember the mornings at the Star Ferry piers in Tsim Sha Tsui and Central, where graceful women in perfectly tailored qipaos and high heels would stride elegantly toward the ferry. They became part of the city’s moving scenery — a vivid memory for countless international visitors and a living emblem of Hong Kong’s style.

This, of course, ties deeply to the evolution of modern Chinese fashion. In Ang Lee’s film Lust, Caution, based on Eileen Chang’s novel, Tang Wei and Joan Chen’s qipaos leave a lasting impression. The film, set between wartime Shanghai and Hong Kong, captures the mysterious allure of that era — even amid espionage and danger, the qipao radiates a soft yet powerful femininity.

Hollywood, too, once fell under its spell. In the 1960s American film The World of Suzie Wong, actress Nancy Kwan portrayed a Wanchai hostess whose cheongsam became an unforgettable visual symbol. Adapted from Richard Mason’s novel, the film captured the qipao’s unique allure and revealed a side of Hong Kong unseen by its own people.

From both international and Chinese perspectives, the qipao stands as a garment deeply rooted in Hong Kong’s local sentiment while carrying forward nearly a century of Chinese aesthetic refinement. It remains one of Hong Kong’s most iconic cultural landscapes — a living testament to the enduring beauty of Chinese artistry.

The qipao, as its name suggests, originated as the attire of the Manchu people during the Qing dynasty. Yet over time, it transformed into a popular garment embraced by the entire Chinese nation, showcasing the elegance and charm of Chinese women. From the 1950s to the 1970s, while the qipao had largely faded on both sides of the strait, Hong Kong stood out as a rare blossom, where women like Maggie Cheung brought a unique Hong Kong style and allure to this traditional dress.

However, after the 1980s, the qipao was gradually overwhelmed by the surge of mass-produced Western suits. Women began replacing qipaos with Western-style ensembles, and the qipao fell out of everyday fashion. The qipaos of my mother’s generation seemed destined to exist only in films and old photographs, becoming objects of nostalgia. I remember returning from the United States in the 1990s and noticing that the once-common sight of qipaos on the streets had nearly vanished. I asked my sisters why, and they found it hard to explain — perhaps Western suits had become cheaper and more widely available, while the qipao gradually disappeared from popular wardrobes.

Yet Hong Kong secondary school girls continued to wear qipao uniforms. They resisted the “de-qipao” trend in fashion, staying loyal to this most traditional Hong Kong garment. Seeing them on their way to school evokes the tradition of Peking University female students wearing Yindanlinen “long cheongsam” uniforms, carrying on the cultural heritage of the May Fourth Movement. Perhaps it is this perseverance of Hong Kong schoolgirls that kept the flame of the qipao alive.

In recent years, a “qipao revival” movement has emerged in Hong Kong. There are now at least a dozen organizations dedicated to revitalizing the “qipao scene,” bringing this once-lost fashion back into popularity. They organize qipao gatherings, donning the latest designs and fabrics, seeking to recapture the charm of the long-missed “Maggie Cheungs.” This marks a kind of artistic renaissance in Hong Kong’s fashion world, allowing more and more women to embrace a forgotten aesthetic, while celebrating the most local and authentically Chinese spirit of the qipao.

The 1970s Chinese Qipao Dress represents a fascinating blend of traditional elegance and the emerging modern trends of that era. Many women admired the 1970s Chinese Qipao Dress for its refined silhouette, exquisite fabric, and intricate detailing. Even today, the 1970s Chinese Qipao Dress continues to inspire designers and fashion enthusiasts who seek to capture the timeless charm of vintage Chinese style. Wearing a Qipao Dress allows one to experience the graceful fusion of culture, history, and fashion.

If you’re interested in exploring more, you can check out our full collection of Qipao Collection and find the perfect piece to match your style and occasion.