What is Hanfu?

Hanfu, the traditional clothing of the Chinese people, embodies a rich cultural heritage. Tracing back to ancient China, Hanfu has evolved over millennia into a fully developed system of attire with its own unique cultural identity. Its distinctive features include a crossed collar, right-side lapel closure, and the use of ribbons instead of buttons for fastening, creating a graceful and flowing visual impression.

Hanfu can be broadly categorized into two main types: formal ceremonial attire and everyday clothing, each suited to different social occasions and daily needs.

Definition of Hanfu

In my view, the standard definition of Hanfu refers to the traditional clothing of the Han Chinese, representing the culture and aesthetic values of ancient China. Its key features include a crossed collar, right-side lapel, wide sleeves, and long skirts, typically fastened with ribbons rather than buttons. Hanfu comes in a wide variety of styles designed for weddings, festivals, ceremonies, and other occasions, each carrying specific designs and symbolic meanings. The revival and popularity of Hanfu today reflect contemporary Chinese people’s respect for and dedication to preserving their traditional culture.

The Dictionary of Chinese Clothing and Attire defines Hanfu as the traditional ethnic clothing of the Han Chinese, worn from ancient times through the end of the Ming dynasty. These garments, with their unique styles and structured designs, reflect the ritual culture and social systems of ancient China. The styles, colors, materials, and decorations of Hanfu all carry symbolic meanings, indicating social status, profession, and marital status. Hanfu encompasses a wide range of categories, including upper garments, lower garments, footwear, hairstyles, makeup, and accessories, each with its distinct style and customs.

Historical Records

In ancient Chinese texts, the term “Hanfu” was often used to distinguish Han Chinese clothing from that of other ethnic groups. For example, in the bamboo slips excavated from the Mawangdui Han tomb (Tomb No. 3), it mentions: “Four beauties, two in Chu attire, two in Hanfu,” using “Hanfu” to refer specifically to Han clothing, in contrast to Chu garments. Cai Yong, in Duan Duan, wrote: “Tongtian Crown: the emperor’s usual attire, received by Hanfu, Qin rites have no record,” indicating that Hanfu was influenced by Qin ceremonial clothing.

The New Book of Tang records instances when Tibetan and Nanzhao troops disguised themselves in “Hanfu” (Tang clothing) to infiltrate and attack Tang settlements, demonstrating how clothing was strategically used in military operations. Other historical texts, such as the Southern Barbarians Biography, describe how local Han people were influenced by the customs of occupying powers, yet preserved Han clothing for ancestral rituals. Northern Song military texts, like Wujing Zongyao, describe captured populations wearing Hanfu, and official records indicate that both Khitan and Han officials in Liao courts wore Hanfu, reflecting a mix of cultural and political symbolism.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Hanfu continued to serve as a marker of identity, tradition, and resistance. For instance, early Qing records describe individuals who insisted on wearing Hanfu in defiance of imposed Manchu dress codes, reflecting loyalty to Han cultural heritage. Even in modern times, Hanfu has been used as a tool for cultural preservation and as a symbol of ethnic identity.

Features of Hanfu

Hanfu, as a representative form of traditional Chinese clothing, showcases the rich history and aesthetic sensibilities of the Han Chinese. Its notable features include the crossed collar with a right-side lapel, wide sleeves and hems, and the use of ribbons for fastening instead of buttons, creating a graceful and flowing visual effect.

Styles and Structure

In terms of structure, Hanfu can be categorized into several types: Shangyi–Xiachang (upper garment and lower skirt), Shenyi (a one-piece robe combining upper and lower garments), and Ruqun (short jacket paired with a skirt). The Shangyi–Xiachang was the basic form of ancient Han attire, with the upper garment covering the torso and the lower garment comprising skirts or trousers. Shenyi, popular from the Han to Tang dynasties, integrates the top and bottom into a single piece. Ruqun, widely worn from the Tang to Ming dynasties, features a short jacket worn over a skirt.

Hanfu headwear is equally diverse, including crowns, scarves, and hats, with different styles and ways of wearing suited for men and women on various occasions. In addition, Hanfu accessories are highly refined, such as belts, jade pendants, and bracelets. These adornments carry not only cultural significance but also aesthetic value. As an essential part of Chinese culture, Hanfu is more than just clothing—it is a carrier of Han Chinese culture and history. In recent years, with the revival of Hanfu culture, an increasing number of people have begun to study and wear Hanfu in their daily lives, expressing respect for traditional culture and a commitment to its preservation.

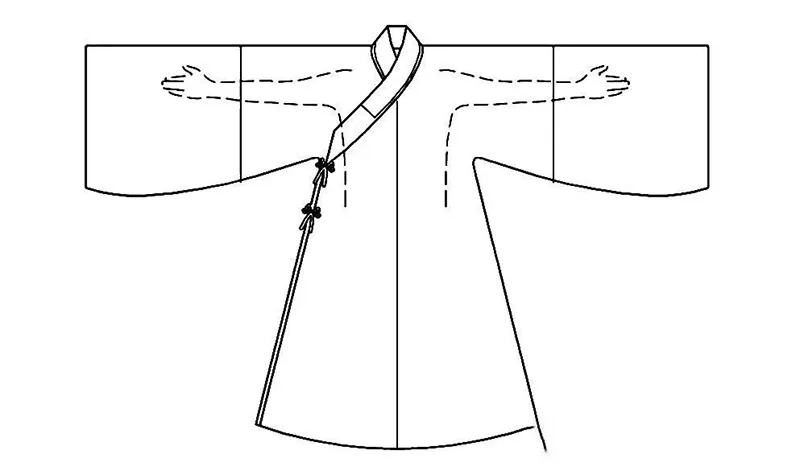

Crossed Collar with Right-Side Lapel

The crossed collar with a right-side lapel, where the garment overlaps to the right forming a “Y” shape, is not only a distinctive feature of Han Chinese clothing but also an important symbol of Han culture. In ancient times, the distinction between the Han and neighboring ethnic groups was reflected not only in language and customs but also in clothing. For example, the Analects mention “beifa zuoren” (wearing the left lapel), which refers to Han people who had been conquered or assimilated adopting the clothing style of other ethnic groups. This was considered a cultural regression and a loss of identity.

In the early Ming dynasty, the government officially designated round-collar robes as the “orthodox attire,” while garments with crossed collars—such as narrow-sleeved shirts and trousers with pleats, braided waist pleats, and two-piece Hu-style clothing (upper garment and lower skirt)—were classified as “Hu clothing” and were to be abolished. This measure reflected the government’s emphasis on preserving Han Chinese traditional culture and its rejection of foreign influences. However, over time, crossed-collar garments with right-side lapels continued to hold a place in both Han and other ethnic clothing, becoming an integral part of traditional Chinese attire. Today, with the revival of Hanfu culture, crossed-collar garments are once again attracting attention and appreciation, serving as a way to inherit and promote traditional culture.

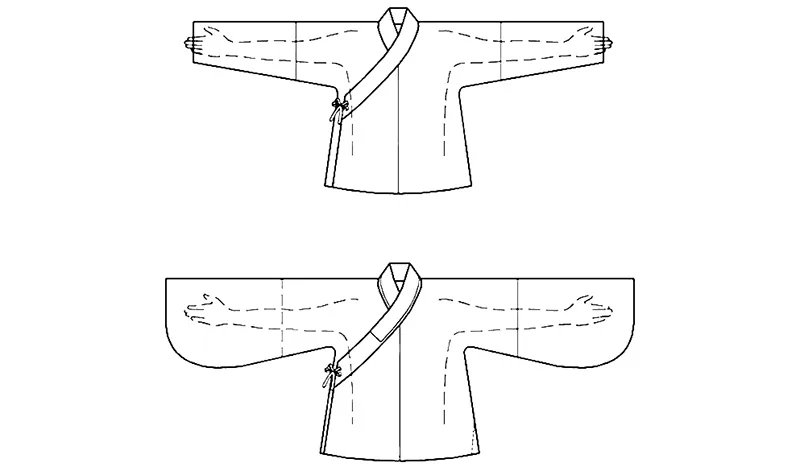

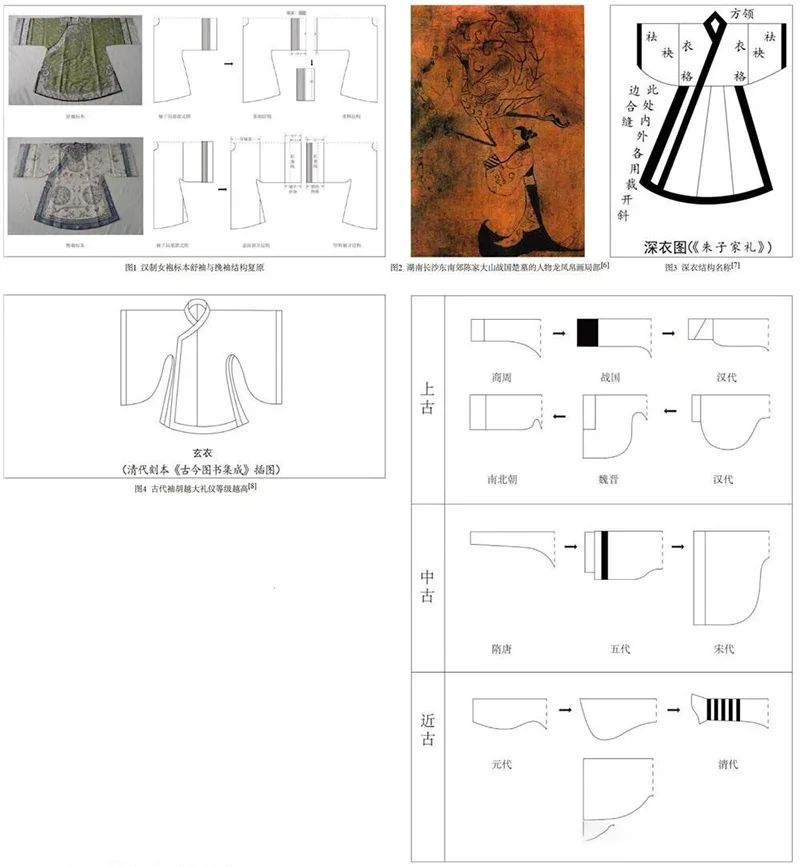

Wide Sleeves (Kuanyi Boxiu)

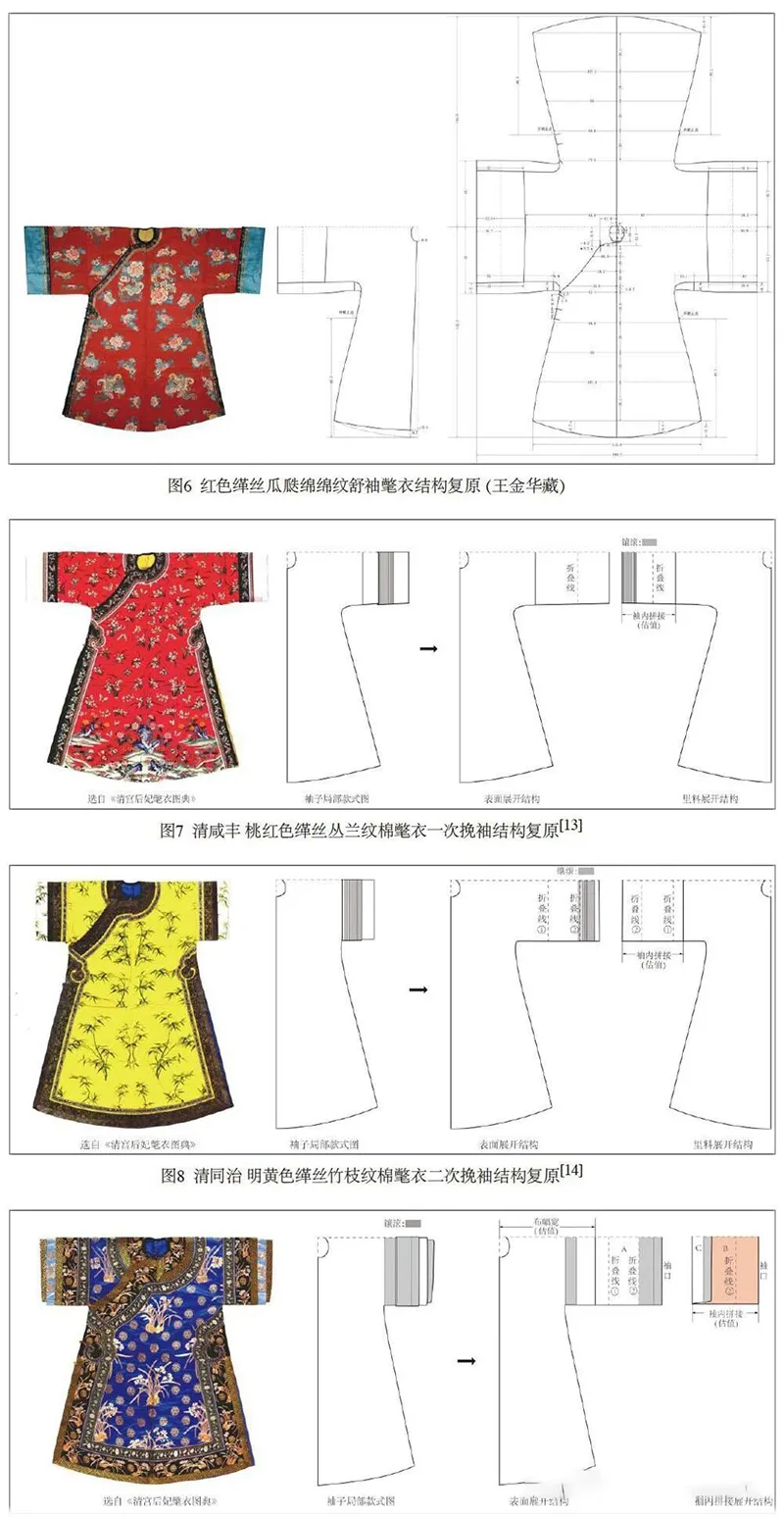

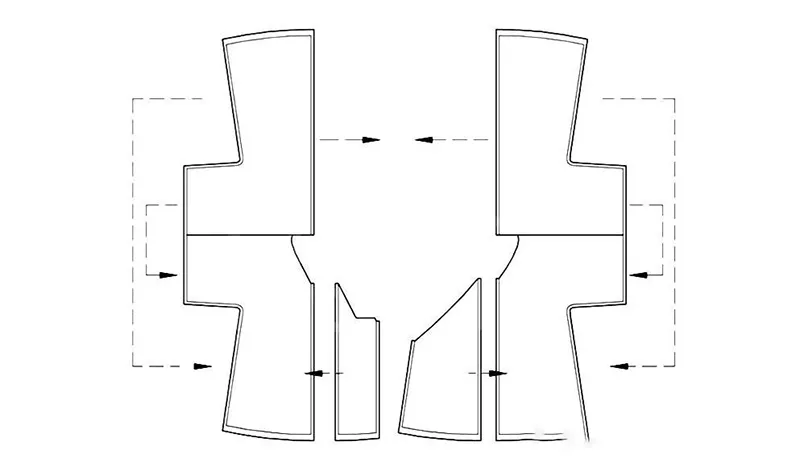

Hanfu with wide sleeves derives its design philosophy from ancient Chinese clothing culture. It is made using a flat-cutting technique, where each part of the garment is individually cut and then sewn together. Unlike modern three-dimensional tailoring, this method allows Hanfu to use ample fabric, creating a loose and flowing visual effect that is both elegant and graceful.

In ancient times, especially among the upper classes such as nobles, officials, and scholars, clothing often featured very wide sleeves with generous breadth and considerable length. Even when the wearer’s arms hung naturally at their sides, the sleeves would not expose the hands and could even cover part of the forearms. This design was not only aesthetically pleasing but also allowed greater freedom of movement, preventing the inconvenience caused by sleeves that were too short.

In ceremonial Hanfu, the sleeves can reach one and a half times the length of the wearer’s arms, designed to “return to the elbow,” meaning the sleeves are long enough to cover the elbow when the arm is bent. The longest sleeves could extend up to four Chinese feet. This design reflects the Han Chinese philosophical concept of “heaven is round, earth is square,” with the rounded, flowing sleeves symbolizing the “roundness of heaven.” In contrast, everyday clothing and military attire feature narrower sleeves, emphasizing practicality and ease of movement. Wide sleeves also serve practical purposes: in the hot summer months, they allow for better ventilation and heat dissipation, enabling the wearer to remain comfortable while maintaining an elegant appearance. Even the clothing of the Manchu people drew inspiration from Hanfu sleeve designs.

Hidden Fastening with Ribbons

In early Chinese clothing, garments were primarily secured with belts, which not only held the clothing in place but also served a decorative purpose. In ancient times, the choice of belt and the way it was worn often reflected the wearer’s social status, rank, and authority, with different materials and styles symbolizing different levels of prestige.

Although buttons were invented and used in China at an early stage, they were not widely adopted before the Ming dynasty and were typically not placed in prominent positions. At that time, buttons were more ornamental than functional, serving as decorative elements rather than the main method of fastening garments. By the mid to late Ming dynasty, buttons became more common, especially in visible areas, likely reflecting changes in social norms, aesthetics, and improvements in clothing design.

In the Qing dynasty, one distinctive feature of clothing was the extensive use of fabric “pankou” (knotted buttons). These buttons were often long and highly visible, used widely across ceremonial robes, official attire, and everyday clothing. This design feature reflects the influence of Manchu culture and the gradual integration of Han and Manchu clothing traditions.

Structure and Components of Hanfu

Traditional Hanfu garments are composed of ten key parts:

Collar (Ling): The design of the neckline.

Front Panel (Jin): The design of the front garment flap.

Hem (Ju): The design of the lower edge of the clothing.

Outer Sleeve (Mei): The outer part of the sleeve.

Inner Sleeve (Qu): The inner part of the sleeve.

Sleeve (Xiu): The overall sleeve design.

Neckband (Jin): The connecting part between the collar and front panel.

Inner Lapel (Ren): The inner lining of the front flap.

Belt (Dai): Used to secure or decorate the garment.

Ties (Xi): Ribbons or straps used for fastening or decoration.

Together, these elements define the unique structure, functionality, and aesthetic of traditional Hanfu.

Ancient Chinese clothing was typically layered in three tiers: xiaoyi (close-fitting undergarments), zhongyi (middle-layer garments), and dayi (outer garments). The xiaoyi included items such as short inner jackets and underpants, while the zhongyi consisted of upper and lower garments, single-layer jackets, and curved-collar tops. The dayi comprised formal robes such as the shenyi, round-collar robes, upper and lower sets, pleated trousers, and ruqun (skirt-and-jacket combinations). In addition, outerwear such as half-sleeve jackets, beizi, and long outer coats were also common. Accessories—including socks, scarves, leather belts, jade belts, and ornaments—were essential components of ancient attire, completing the overall ensemble.

In ancient China, cloth was one of the forms of tax levied on the people, and the standard width of the fabric was typically 2 feet 2 inches (about 50 centimeters). Traditional Hanfu was usually made from hand-woven cloth of this width. When constructing a Hanfu, two pieces of equal length were folded and used for the front panels and back hem. The back seam created during sewing was called the ju. If the front panels lacked an inner flap (ren), the garment was called a straight-collar overlapping robe. When flaps were sewn onto both sides of the front panels, it became a right-overlapping collar (youren). The hem length varied: waist-length (covering the waist), knee-length, and foot-length (covering the top of the feet).

Hanfu Styles and Types

In ancient Chinese clothing culture, the styles and structures of garments reflected strict social hierarchies and rich cultural meaning. Clothing was generally categorized into ceremonial attire, auspicious attire, everyday attire, and casual attire, each serving distinct social and cultural functions.

Ceremonial Attire: Also known as formal clothing, worn during grand ceremonies and rituals. The most representative example is the mianfu, worn by emperors and officials during court assemblies and sacrificial rites. It typically featured a two-piece structure with an upper garment and lower skirt, a round-collar top with overlapping front, and a trapezoid-cut skirt. Designs varied slightly between men and women.

Auspicious Attire: Worn on celebratory occasions such as festivals or weddings, usually in bright colors with auspicious patterns.

Everyday Attire: Worn in daily life; men typically wore robes (paoshan), while women wore the ruqun.

Casual Attire: More relaxed garments, worn in informal settings.

Ruqun

The ruqun served as the primary form of women’s everyday attire. Its history is long, and its styles are varied. The ru is a short upper jacket, while the qun is a skirt worn on the lower body. Although the specific designs and colors of the ruqun changed with dynasties and fashion trends, its overall structure remained relatively consistent.

Discover the timeless beauty and elegance of traditional Chinese clothing by exploring our curated collection of Hanfu. From ceremonial robes to everyday ruqun, each piece reflects centuries of Chinese culture and craftsmanship.

Browse the full range and find your perfect Hanfu here: Aslinfashion Hanfu Collection.

The styles and variations of ancient clothing not only reflect the customs and practices of historical societies but also reveal the aesthetic ideals and social changes of different periods. Studying ancient attire is therefore essential for gaining deeper insight into the culture and daily life of past civilizations.

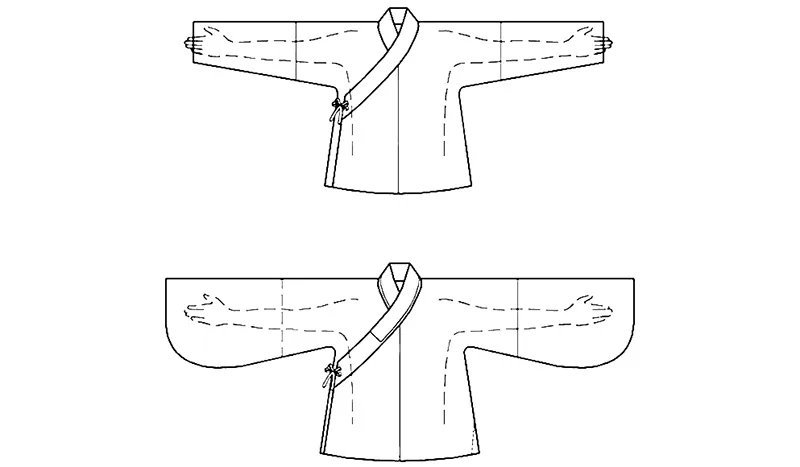

Shenyi (Deep-Robe)

The Shenyi is a form of ancient clothing rich in cultural significance and historical evolution. For Confucian scholars, the Shenyi was more than just clothing; it symbolized moral cultivation, scholarly refinement, and the ideals of Confucian learning.

Records in the Liji Zhengyi: Shenyi provide a glimpse of its original form. The Shenyi is characterized by its loose fit, floor-length hem, wide sleeves, and overlapping front panels, embodying the Confucian aesthetic of moderation and harmony. Wearing the Shenyi also followed precise etiquette, reflecting the Confucian emphasis on refined behavior and decorum.

By the Song dynasty, the Shenyi had become a marker of scholarly status and intellectual identity. Song Confucian scholars placed great importance on rituals, and the Shenyi played a central role in their daily attire. Over time, the styles and materials of the Shenyi evolved, but its symbolic representation of Confucian culture and values remained constant.

By the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, the Shenyi had become even more diverse in form, yet its role as a symbol of a Confucian scholar’s status remained firmly established. During this period, the Shenyi saw innovations in design, such as standing collars and overlapping fronts, while also embracing more luxurious materials and elaborate decorations, reflecting the elevated status of scholars and the prosperity of society.

Ma Duanlin, in Wenxian Tongkao, provides detailed records of changes in Song and Yuan clothing, allowing us to trace the development of Chinese clothing culture. The evolution of the Shenyi serves as a vivid example of the interplay between Confucian culture and traditional Chinese attire. Overall, as a significant component of traditional Chinese clothing, the history of the Shenyi not only embodies the transmission and development of Confucian culture but also mirrors societal changes and progress. Its story represents a fascinating chapter in the history of Chinese clothing culture.

Outer Garments

Outer garments, such as the beizi, half-sleeve jackets, cloaks, and hechangyi, were not only innovative in form but also carried their own cultural significance. The evolution and popularity of the beizi, along with the emergence of cloaks, are notable points in the development of clothing culture. The styles and characteristics of these garments reflect the customs, rituals, and cultural values of ancient Chinese society.

Beizi

Ancient Chinese outerwear was diverse, with each type possessing a unique history and style. The beizi, evolving from the half-sleeve jacket or zhongdan, was characterized by its simple yet elegant design. Its history can be traced back to the Tang dynasty, and it became particularly popular during the Song dynasty. Yan Fan Lu: Beizi, Zhongchan describes the beizi as: “Resembling a single-layered jacket with added length at the hem, falling straight to the feet.” This description provides a glimpse of the beizi’s original form and style.

The beizi carries a rich historical legacy in its very name. Cheng Dachang, in Yan Fan Lu, notes that the beizi evolved from the ancient zhongchan. The zhongdan resembled what we might consider a modern vest, while the beizi extended the hem, creating a distinct style of outer garment. During the Song dynasty, the beizi became a common attire for court women, particularly the empresses of the Song and Ming dynasties, who often wore red silk beizi for formal occasions.

Over time, the beizi gradually evolved into the cloak. This transformation is evident in the Ming dynasty, when cloaks retained the loose cut and comfortable fit of the beizi, while developing their own distinctive style. The emergence of the cloak not only enriched the variety of ancient outerwear but also provided inspiration and a foundation for later clothing designs.

Throughout the evolution of ancient Chinese clothing, both the beizi and cloaks played pivotal roles. From the elegant court attire of the Tang and Song dynasties to the everyday wear of the Ming dynasty, they bear witness to the development of clothing culture and reflect the social and aesthetic changes of each period.

Hanfu Regulations and Garment Standards

In ancient China, ceremonial and sacrificial garments were strictly regulated in terms of color, dimensions, and design, with rules varying according to social status. Official attire, court clothing, and noblewomen’s garments followed precise specifications, while everyday and auspicious attire generally had fewer restrictions. Even so, everyday clothing sometimes reflected social hierarchies—for example, nobles wore large-sleeved, long-hemmed robes, whereas commoners and scholars wore shorter jackets with smaller sleeves.

During the Ming dynasty, regulations even specified: “Commoners’ robes should fall five inches above the ground, sleeves extending six inches past the hand, sleeve width one Chinese foot, and sleeve openings five inches. Soldiers’ robes fall seven inches above the ground, sleeves extend five inches past the hand, sleeve width no more than one Chinese foot, and narrow sleeves no more than seven inches.” Nevertheless, some dynasties often witnessed breaches of these regulations, a phenomenon known as shecheng.

The portrait of Lu Shusheng in court attire shows him wearing a liangguan (beam-shaped crown). This particular crown features five beams, a style reserved for third-rank officials. Lu Shusheng (1509–1605) was a Ming dynasty official from what is now Shanghai.

Royal and Noble Attire

In ancient China, the emperor and male members of the immediate royal family wore the mianfu as formal ceremonial attire, paired with the mian crown. Nobles during the pre-Qin period wore the xuanduan, used for sacrificial ceremonies, court appearances, coronation rituals, and weddings.

Sacrificial garments also included the suduan. These garments were all in the form of overlapping collars with right-side closure (youren), featuring wide sleeves and an upper-and-lower garment structure. After the Tang dynasty, the xuanduan was no longer used as sacrificial attire, and separate ceremonial garments were established.

The pibianfu was another type of formal ceremonial robe for royal men. The empress and crown princess wore the zhaoyi, a long-sleeved robe with continuous upper-and-lower construction. During the Ming dynasty, other female members of the royal family wore garments such as the juyi and dashan, often paired with the phoenix crown and xiapei (decorative scarf). The juyi was a two-piece deep-robe style with a round collar.

For daily formal wear, the emperor and close royal family members commonly wore the gunlongpao (imperial dragon robe). The emperor’s gunlongpao was usually yellow, earning it the name “yellow robe.” Most gunlongpao featured a round collar adorned with dragon patterns, though some versions were designed with overlapping collars (jiaoling).

Ming Shenzong, Zhu Yijun (September 4, 1563 – August 18, 1620), styled Yuzhai, was the 13th emperor of the Ming dynasty and the third son of Ming Muzong, Zhu Zaihou. His mother was Empress Dowager Xiaoding, Lady Li. He reigned for 48 years, making him the longest-reigning emperor of the Ming dynasty.

Attire of Officials and Nobles’ Wives

The clothing worn by officials was referred to as guanfu (official robes), with court attire (chaofu) worn during imperial audiences. In the Song dynasty, officials’ court robes featured square-collared jackets (fangxin quling), and their headgear varied according to rank, including the jinxianguan, diaochanguan, or jiezhi guan.

During the early Ming dynasty, court robes consisted of red silk garments with blue trim—chiluoyi (red silk jacket) and chiluoshang (red silk skirt)—paired with the liangguan (beam-shaped crown). Ming dynasty officials also had ceremonial robes for official sacrifices, typically consisting of qingluoyi (blue silk jacket) and chiluoshang, also featuring the square-collared design (fangxin quling). During official sacrificial ceremonies, Song and Ming dynasty officials would don these ceremonial robes to perform their duties.

Official Attire

Gongfu was the formal uniform of officials. From the Tang to Ming dynasties, official ceremonial robes were generally round-collared gowns (yuanlingpao). During the Tang and Song dynasties, the colors of these robes were assigned according to rank, typically purple, vermilion, green, and blue, and officials wore the zhanjiao futou headgear. In the Ming dynasty, ceremonial robes were colored in scarlet, blue, or green according to rank, and were worn only on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar month for court audiences; on other days, officials wore their everyday official robes (guanchangfu). Ming everyday robes often featured embroidered rank badges (buzu), also called bufu, with no strict color requirements, and came in both round-collared and overlapping-collar designs.

The formal attire of noblewomen (mingfu) included the long robe (dashan) paired with the decorative scarf (xiapei) and the zhaiguan crown. Ordinary formal attire for women consisted of round-collared robes or jackets paired with skirts, often decorated with rank badges. Meritorious officials and their wives could be granted the special mangfu (python robe) by the emperor as an honor.

Clothing of Commoners and Scholars

For common men and scholars, formal attire from the pre-Qin to Han dynasty included straight-hemmed robes (zhiju pao) and curved-hemmed robes (quju pao), which were worn by both men and women. In later periods, men’s regular and ceremonial attire mostly consisted of long robes (pao), while women’s regular and ceremonial attire usually included jackets (shan) paired with skirts (qun).

Everyday clothing (bianfu) for men and women included the simple two-piece garments of jacket and trousers (shangyi xiaoku), suitable for physical labor or sports. Women’s casual clothing also included narrow-sleeved jackets and skirts (zhixiu shanqun).

Children’s Attire

In the Ming dynasty, Han Chinese children’s clothing, whether wearing a headband (guzi), a round-collared jacket (yuanlingshan) on the left, or a cloak (pifeng) on the right, generally differed little from adult garments. The most common style consisted of a jacket and trousers, though some children also wore short jackets (banbi) or pants alone (kun), while full-length robes were less common.

During the Tang and Song dynasties, girls often wore ruqun (jacket and skirt), and by the Ming dynasty, girls frequently wore aoqun (long jacket paired with skirt).

Infant and Toddler Attire

Some very young children wore only undergarments such as dudou (bellybands), leg-wrapped undergarments, moxiong (short chest covers), or liangdang (crotch coverings). Infants often wore open-crotch pants and bibs (weiwei, also called xianshidou), frequently cut in petal or plum blossom shapes, sometimes in other designs, and often embroidered with auspicious patterns. Toddlers who could control their urination and defecation transitioned to closed-crotch pants.

Although the Qing dynasty implemented the policy of shaving the head and changing clothing, the custom of dressing young children in Ming-style garments persisted due to the principle of “the old follow the young not the young follow the old.” The overlapping-collar and right-crossing design (jiaoling youren) with tie closures is gentle on infants’ delicate skin and carries the cultural meaning of teaching children not to forget Ming clothing traditions and ancestral attire; this style is commonly referred to today as “monk-style clothing.”

Children’s headwear differed from adults’. Infants and toddlers often wore tiger-head hats, believed to ward off evil spirits and provide protection and strength. Other headwear included guzi (headbands, also called mo’e, e’gu, ezi, or circular hats), sometimes decorated with tigers, flowers, or plain designs. There were also wind hats, with extended backs to shield from the wind. Some headwear was similar to adult styles, such as square scarves (fujin). Footwear included regular shoes, as well as animal-shaped shoes like tiger-head or pig-head shoes for infants and toddlers.

Wedding Attire

Traditional Chinese weddings did not have a separate, exclusive set of garments. Instead, auspicious ceremonial attire (jifu) was typically worn. In the pre-Qin era, the wedding of scholars (shihunli) required the groom to wear the juebian (official cap) and red and black robes (xunshang zi yi), with black-edged skirts; the term yi refers to the edge trimming. The bride wore a red-trimmed black robe (chunyi xunyi), where yi similarly refers to the trimmed edges. Other wedding procedures followed the appropriate dress codes for social rank: wives of high-ranking officials wore white robes (zhanyi), while wives of commoners wore black robes (puyi) as ceremonial attire.

As recorded in Liji Zhengyi – Zengzi Wen: “For wedding attire, the wife of a scholar wears puyi, the wife of a grand official wears zhanyi, and the wife of a minister wears juyi.” According to the Zhou ritual system, brides from common families wore black puyi, the wives of high-ranking officials wore white zhanyi, and the emperor’s principal wife wore the ceremonial yi robe upon formal investiture.

Wedding Attire in the Tang and Song Dynasties

During the Tang and Song dynasties, the groom’s wedding attire depended on his official rank. Grooms of the fourth rank and above wore the ceremonial mianfu, while those of the ninth rank wore the juebian robe, and commoners wore the crimson-red round-collared robe (jianggongfu). Brides would dress according to the groom’s rank. In the early Tang dynasty, brides wore the huachi ceremonial robe, a deep-robe (shenyi) style formal garment. Later, the huachi robe gradually fell out of use, and brides began to wear wide-sleeved ruqun, often in green. Pairing a green-clad bride with a groom in a red round-collared robe became known as “Red Groom, Green Bride.”

In the early Song dynasty, Tang wedding customs were initially maintained, but later brides adopted the fengguan xiapei (phoenix crown with long veil) ensemble for weddings, a practice that continued into the Ming dynasty. In Ming official weddings, grooms wore regular official attire according to their rank, while brides wore ceremonial women’s attire reflecting their husband’s rank. Commoners could imitate ninth-rank official attire or the regular attire of ninth-rank officials, though violations of protocol occasionally occurred. Some opted not to wear official garments at all, with grooms in paofu (robes) and brides in aoqun (jacket and skirt) as their wedding attire.

Funeral Attire

Traditional Chinese mourning garments were determined by the “Five Grades of Mourning” (wufu), a system that specified the length of mourning and the coarseness of clothing depending on the deceased’s relationship to the mourner. The heaviest mourning garment, zhancui, was made from coarse hemp cloth with unhemmed edges. The next grade, qicui, was made from processed hemp and had neatly hemmed edges. The third grade, dagong (also called “big red”), was finer than qicui, made from processed hemp. Xiaogong (or “small red”) was finer still, followed by sima, the lightest and most delicate.

In the Ming dynasty, when an emperor or empress passed away, officials wore zhancui: their wushamao hats had their wings removed and were wrapped in white cloth, paired with plain-colored round-collared robes, hemp waist cords (yaodui), and hemp shoes. After the mourning period, they switched to plain attire with black corner belts, returning to regular clothing after one hundred days. Widows wore hemp round-collared robes, hemp skirts, and hemp shoes, covering their heads with hemp cloth; they removed mourning attire after twenty-seven days.

The “Five Grades of Mourning” and Filial Attire

The traditional Chinese system of the “Five Grades of Mourning” (wufu) was quite complex and was often simplified in later dynasties, commonly referred to as filial attire (xiaofu). After the formal mourning period, mourners would return to wearing regular clothing but would choose more subdued colors. Women would minimize the use of ornate headpieces and jewelry. In the Ming dynasty, for example, women would switch from their usual black or gold-threaded hairstyles (di ji) to white mourning hairstyles (xiaoji). Servants attending the household during mourning would wear white garments and white hats.

Collar Styles in Hanfu

The collar of a Hanfu garment is a crucial design element, with various shapes and styles that distinguish different types of traditional clothing. Common collar types include:

Straight Collar (Zhi Ling): A straight collar hangs vertically without encircling the neck. When paired with overlapping lapels, it is often called a crossed collar (jiaoling).

Round Collar (Yuan Ling): Also called a “pan collar,” this type forms a closed, curved line around the neck. Round collars are common in Hanfu, especially in women’s garments.

Square Collar (Fang Ling): A square collar features edges that are rectangular or near-square in shape. This style is less common but appears in certain traditional Hanfu designs.

Standing Collar (Shu Ling): Based on the straight collar, the front edge is raised to stand vertically, fully enclosing the neck. This style has gained popularity among modern Hanfu enthusiasts and is sometimes referred to as a “stand-up collar.”

The choice of collar is not merely decorative; it also reflects historical periods and cultural contexts. In Hanfu terminology, “ling” (collar) can also serve as a unit of measure for upper garments. For example, a garment may be described as “a round-collar shirt” (yuanlingshan) or “a standing-collar jacket” (shuling ao), indicating the collar style as a key feature of the attire.

Ancient Chinese textiles were remarkably diverse, with each material possessing its own unique qualities and applications. Common types of traditional fabrics included gold-thread brocade (jinlü), brocade (jin), gauze (luo), damask (ling), silk (juan), fine linen (jian), hemp (ma), cotton (mian), and many more.

Gold-thread brocade, brocade, gauze, and damask were among the most luxurious fabrics in ancient China. Brocade and damask, in particular, were prized for their beauty and intricate weaving techniques. These materials were often reserved for imperial court attire, aristocratic garments, and high-end decorations. Throughout history, “silks and brocades” (ling luo jin xiu) symbolized wealth and social status.

During the Qin and Han dynasties, several regional fabrics gained national fame. For example, Qi’s fine white silk (qi wan) and Lu’s delicate linen (lu gao) were highly valued, while Wu’s damask (wu ling), Yue’s gauze (yue luo), Chu’s silk (chu juan), and Shu’s brocade (shu jin) became famous for their superior craftsmanship and quality. Each region developed distinct textile traditions that reflected its local resources and aesthetic preferences.

Hemp and ramie (ma ge) were among the oldest and most affordable textile materials. Known for their durability and breathability, they were commonly used to make everyday garments and work clothes, especially among the laboring class.

The famous Yuan dynasty poem “Yi Zhi Hua: To a Beauty” by Tang Shi contains the line, “Priced as high as Qi silk and Lu linen, famed as Shu brocade and Wu damask,” highlighting how the fine silk from Qi and the linen from Lu were as costly as the exquisite brocades from Shu and Wu—each representing both craftsmanship and cultural prestige in ancient China.

Hanfu Dyeing, Printing, and Accessories

In the Zhouli (Rites of Zhou), ancient Chinese texts already recorded officials known as Diansi and Ranren who were responsible for silk production and dyeing. Traditional dyeing materials were entirely plant-based, including safflower, black plum, sumac, sappanwood, phellodendron, indigo, pagoda tree flowers, cudrania, bayberry bark, indigo leaves, lotus seed shells, and even mung bean powder.

Classical textile dyeing in ancient China followed the cosmological principles of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, which deeply influenced the symbolism of color. There were six primary colors, each corresponding to a cosmic direction or natural element:

Blue (Qing) symbolized the East and Wood,

Red (Chi) symbolized the South and Fire,

White (Bai) symbolized the West and Metal,

Black (Hei) symbolized the North and Water,

Dark (Xuan) represented Heaven,

Yellow (Huang) represented Earth.

In addition to these six fundamental tones, there were intermediate colors—such as orange-yellow, purple-red, rose, greenish-yellow, and pale blue—used in official garments during the Tang and Song dynasties. These variations denoted official ranks, with court robes ranging from scarlet, purple, and crimson to green and blue.

Among the most accessible and widely used textiles was indigo-dyed printed cloth, also known as blue calico or dyed floral cloth (药斑布, “yaobanbu”). Using natural indigo extracted from woad plants, artisans employed a resist-dyeing technique with stencils and paste to create delicate white patterns on deep blue backgrounds. This technique, which dates back over 1,300 years, originated during the Qin and Han dynasties and flourished in the Tang and Song periods.

The Han Chinese developed three major dye-resist techniques collectively known as the “Three Xie” (Sanxie):

Wax-resist dyeing (Laxie),

Clamp-resist dyeing (Jiaxie),

Tie-dyeing (Jiaoxie).

The term “xie” refers to the act of tying or clamping fabric before dyeing to create intricate patterns—a process that can be traced back to the Qin and Han eras. During the Ming dynasty, the popularity of brocade weaving and embroidery gradually replaced the older clamp-resist method, giving rise to alkali printing, rubbing, and paste-resist dyeing techniques.

Hanfu textile craftsmanship continued to evolve through the centuries, flourishing in renowned regional embroidery styles such as Su Embroidery (Suzhou), Xiang Embroidery (Hunan), Shu Embroidery (Sichuan), Yue Embroidery (Guangdong), and Han Embroidery (Hubei)—as well as in the exquisite brocades of Shu, Yun, and Song. Among all, Kesi silk tapestry represented the pinnacle of weaving artistry. Originating in the Tang dynasty, it used raw silk as the warp and dyed silk (often with gold threads or peacock feathers) as the weft, creating luxurious multi-colored patterns—sometimes using more than seventy hues in a single piece.

Headdresses and Headwear

Headwear was a crucial component of Han Chinese attire, symbolizing status and virtue. Various forms included mian guan (crown with pendants), jue bian (ceremonial cap), pi bian (leather cap), wei bian (military cap), tongtian guan (celestial crown), zhang guan (long crown), fujin (head scarf), and wumao (black gauze cap).

For emperors and nobles, the mian guan was worn during grand ceremonies such as ancestral sacrifices. The crown featured a rectangular board—rounded at the front and square at the back—with rows of hanging strings of beads called miandiu. The number and material of these beads distinguished social rank; the emperor’s crown had twelve bead strings made of jade, signifying supreme authority. The cap itself was black, and on each side were holes through which a jade pin (ji) was inserted to secure it to the hair bun. Two silk ribbons tied under the chin, with decorative jade beads called chonger hanging at each ear. Interestingly, these beads were not worn inside the ears; they served as a moral reminder to avoid listening to slander. The modern Chinese idiom “to turn a deaf ear” (充耳不闻) originates from this ancient practice.

The liang guan (beam crown), derived from the jinxian guan of the Warring States period, was the traditional headwear for civil officials. The long guan, also known as the wu guan or huiwen guan, was the counterpart for military officers. Together, these headdresses reflected the harmony between civil virtue and martial valor that lay at the heart of traditional Chinese aesthetics.

In ancient China, adult Han men and women typically tied their hair into buns on top of their heads, secured with hairpins known as ji (笄). Men often wore various types of headgear, including crowns, scarves, and hats, each with distinct styles. Children’s headwear included tiger-head caps and flower hats, which were both decorative and symbolic.

Women’s hairstyles were richly diverse. They often adorned their hair buns with pearl flowers, dangling ornaments (buyao), kingfisher-feather hairpins, and comb-shaped crowns. Some styled their temples with side ornaments (bo bin), while others wore veiled hats or wrapped headscarves. The custom of inserting combs and hairpins dates back to the Han dynasty, and by the Southern dynasties, women were fond of decorating their buns with ornamental combs. During the Tang dynasty, inserting multiple hairpins and combs became highly fashionable. Han women also had the custom of wearing silk flowers in their hair — as the saying goes, “In her jeweled bun, flowers bloom.” According to legend, the Queen Mother of the West once saw Emperor Wu of Han with a large flower in his hair bun.

By the Ming dynasty, noble families, such as the Confucius household, maintained estates dedicated to cultivating flowers for decoration, as well as for palace maid training in traditional hair ornaments and floral attire. In the mid-Ming period, the forehead band (mo’e) became popular again, used to partially cover the forehead as a beauty accessory.

Footwear

Hanfu footwear included socks, xi, lü, ju, ji, boots, and shoes. Ancient texts say that after the reigns of Yao, Shun, and Yu, people began to wear wooden clogs. Yi Yin is said to have made straw sandals and silk shoes. The oldest known pair of wooden clogs in China was unearthed at the Cihu Neolithic site in Cicheng Town, Ningbo — a relic of the Liangzhu culture. In the Zhou dynasty, people wove shoes from hemp. Ji referred to wooden shoes with raised soles (similar to geta), commonly made from paulownia wood in southern China, with rush or hemp straps. Straw sandals were believed to have been invented by one of the Yellow Emperor’s ministers. Boots, meanwhile, were introduced by Zhao Wuling King after he adopted nomadic attire and horseback riding.

Women’s shoes were often embroidered with floral patterns and known as xiuhua xie (embroidered shoes). Infants and young children wore charming animal-themed shoes, such as tiger-head or pig-head shoes, believed to ward off evil and bring good fortune.

History

For thousands of years, successive dynasties of the Chinese civilization faithfully upheld and transmitted the Zhou ritual dress system. While maintaining the core Confucian ideals of propriety and hierarchy, each era also adapted its clothing to meet the cultural and aesthetic needs of the time — gradually forming distinct styles that reflected the characteristics of each dynasty. These everyday garments (changfu) differed across periods, with detailed regulations on permissible colors, patterns, and designs for various social ranks, clearly revealing the identity and order of each era.

Pre-Qin Period

Ancient Times

According to the Shiben from the Han dynasty, “Baiyu, a minister of the Yellow Emperor, created clothing,” and “Hu Cao made ceremonial robes and crowns.” The Book of Changes (Yi Jing, Xi Ci section) records, “The Yellow Emperor, Yao, and Shun let their garments hang down, and the world was well governed,” symbolizing the civilizing power of clothing and ritual. The Records of the Grand Historian (Shi Ji, “Annals of the Five Emperors”) notes that the Yellow Emperor’s wife, Leizu, raised silkworms and invented silk production, allowing garments to be woven from fine threads. Tang scholar Zhang Shoujie later commented in Annotations to the Records of the Grand Historian that “the Yellow Emperor built houses and created clothing,” marking the beginning of structured attire in Chinese civilization.

According to Wang Yi’s Jifu Commentary, in ancient times, people wore animal hides as clothing. Starting from the eras of Fuxi and the Yan Emperor (Emperor Yan), true garments made from woven materials began to appear. By the time of the Yellow Emperor, a more complete system of dress — including ceremonial robes and crowns — had already taken shape.

Archaeological discoveries support this progression. At the Peiligang cultural site (7,000–8,000 years ago) and the Baijia Village site in Lintong, Shaanxi, bone needles and spindle whorls have been unearthed — clear evidence that people at that time already knew how to spin and weave fabric. By the Yangshao culture (around 5,000 years ago), spindle whorls became widespread, and pottery shards often bore impressions of woven cloth. Remains of ramie fibers and silkworm cocoons found at sites from the same period further indicate the rise of primitive agriculture and textile production. People had begun making clothes from ramie linen and silk threads produced through sericulture, marking a significant advancement in dress and adornment.

Although no actual garments from this period have yet been discovered archaeologically, ancient texts record clear distinctions in clothing among early dynasties: the Xia people favored black robes, the Shang preferred white garments, and the Zhou adopted a balanced approach — wearing dark upper garments and light-colored lower robes, combining the traditions of their predecessors.

During the Shang dynasty, clothing styles were characterized mainly by two types. One was the full-length robe — a single-piece garment often worn by women or slaves. The other, more formal type, consisted of a separate upper garment (yi) and lower garment (shang). The upper garment came in various designs, including cross-collared and straight-front styles, usually with wide collars and narrow sleeves. The lower garment was either a long skirt or an open-crotch trouser. A broad sash was tied around the waist, with a bi (decorative apron-like panel) hanging down in front.

Shang nobles typically wore brightly colored silk robes and layered them with ornate silk brocade outer garments (xi), which featured woven, embroidered, or painted patterns. The cuffs and collars were often trimmed with decorative lace, and jade ornaments were commonly used as accessories. Headwear became a key symbol of rank and status — leading to the development of ceremonial crown systems. Different types of headgear included crowns, ceremonial caps (mian), simple hats, and hairpins (ji).

In contrast, commoners and slaves wore coarse hemp garments and did not wear crowns or hats.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, clothing largely continued the Zhou dynasty system, though with slight modifications. The philosophical schools of the time — such as Confucianism — influenced dress regulations, integrating clothing into the framework of “ritual governance.” Thus, garments became an expression of propriety and hierarchy, and China’s system of ceremonial attire grew increasingly refined.

Belts were commonly used to fasten clothing, often secured with hooks and sometimes adorned with jade pendants. The shenyi (deep robe) and pao (long robe) emerged during this period — the pao typically appeared in two main forms: the quju pao (curved-hem robe) and the chanyu (straight-hem robe). The ruqun (blouse and skirt combination) also came into use.

In the Qin and Han dynasties, clothing styles continued to evolve from those of the Warring States. Robes were mainly divided into two types by their cutting patterns: the quju pao (curved-hem robe) and the chanyu zhiju (straight-hem robe). Both men and women could wear these styles. Warriors, on the other hand, typically dressed in short jackets with narrow sleeves and wide trousers, suitable for movement and combat.

During the Qin and Han dynasties, the quju robe (curved-hem robe) was the most common style of women’s clothing. This garment was form-fitting, with a long sweeping hem that often trailed on the ground, giving the skirt a flared, bell-like shape that concealed the wearer’s feet when walking.

The Han-style deep robe with a wrapped front featured narrow sleeves and a tight silhouette. The garment wrapped around the body several times before being fastened at the hips with a silk belt. The fabric was often decorated with refined and elaborate patterns. Sleeves came in both wide and narrow forms, and cuffs were typically bordered with trims. The collar was cross-shaped (jiaoling), cut low to reveal the inner garment. It was common to wear multiple layers, each with a visible collar — sometimes as many as three, a style later referred to as the “three-layered robe.”

As robes became increasingly popular, the number of women wearing ruqun (blouse and skirt) decreased, though the style never disappeared completely. Han dynasty folk songs and poetry still described women in ruqun. Typically, the blouse (ru) was very short, ending at the waist, while the skirt (qun) was extremely long, trailing to the ground. A real example of a ruqun from this period was unearthed in 1957 from a Han tomb in Mozuizi, Wuwei, Gansu Province.

During the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, aristocratic men and their attendants adopted clothing that reflected strong influences from northern nomadic tribes. Ancient scholars recorded that by the Jin dynasty, Han clothing had been deeply influenced by foreign (Hu) styles, and this trend “continued to be inherited thereafter.” By the Northern Qi dynasty, “the attire of the Central Plains had completely adopted Hu dress — featuring narrow sleeves, red-green short coats, high boots, and dangling belt ornaments — all typical elements of Hu-style clothing.”

Narrow sleeves made archery and horseback riding easier, while short garments and tall boots were practical for life on the steppes. By this time, everyday clothing in much of China — such as high-collared shirts, boots, and fitted tunics — had largely taken on the characteristics of Hu-style attire.

“The crowns and robes of the ancient kings have all been swept away. The disorder in attire and headgear in the Central Plains began with the Five Barbarians during the Jin dynasty and continued through successive eras: Tang succeeding Sui, Sui succeeding Zhou, and Zhou succeeding the Northern Wei — by and large, Hu-style clothing prevailed.”

Sui, Tang, and the Five Dynasties period

During the Tang dynasty, there was a broadly inclusive attitude toward foreign clothing and headgear, and various external influences both shaped and transformed Tang fashion culture. For men, everyday attire favored the futou robe and tunic. The futou, also called futou headwrap, evolved from the fu jin headwraps of the Northern Han and Wei dynasties.

Officials, while wearing narrow-sleeved round-collared robes for daily use, would don ceremonial attire on important occasions such as sacrificial rites. The ceremonial garments largely inherited styles from previous dynasties: officials wore jiefa or longguan headpieces, cross-collared robes with wide sleeves, wrapped skirts, and accessories such as jade pendants and sash ornaments.

The predecessor of the futou was the fu jin or square headscarf, in use since the Eastern Han dynasty. It was later modified from the Xianbei hat and classified as a form of “Hu-style” attire. During the reign of Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou, the headscarf was further adapted: ties were sewn onto its four corners, and a unique tying method was invented, where one pair of ties was fastened at the back of the head while the other pair was looped forward and knotted over the front of the topknot. This design was also called the “folded headscarf”. The futou was originally created “for ease in military affairs,” using lightweight silk or gauze to bind the hair tightly, keeping it neat and unobstructed for archery. Between the Sui and Tang dynasties, to achieve a more elegant appearance, a stiff inner cap was added. From the Tang through the Song dynasty, the corners of the headscarf evolved into decorative hat wings, and sturdier lacquered gauze became the main material, eventually forming the black gauze hat (wusha mao). During the Five Dynasties period, clothing largely followed Tang styles.

Song Dynasty

During the Song dynasty, Han Chinese men’s casual attire continued the tradition of cross-collared right-over-left robes and round-collared robes. Han women mainly wore shanqun (tunic and skirt), which came in two basic styles: cross-collared and straight-collared tunics. Women’s clothing featured greater variation than men’s, including the emergence of the beizi.

The shenyi is a traditional Chinese garment recorded in pre-Qin texts, which had largely disappeared by the Han dynasty but was reinterpreted or reconstructed by Song scholars such as Zhu Xi. Texts like the Book of Rites mention the shenyi as a simple ceremonial garment. By the Han dynasty and afterward, it existed more as a legendary reference than a commonly worn attire. In the mid-Northern Song, scholars like Zhu Xi and Sima Guang reconstructed the shenyi based on ancient records and wore it as everyday clothing. On one occasion, Sima Guang asked the scholar Shao Yong, “Sir, might you wear this garment?” Shao Yong replied, “I live in the present; I wear the attire of our time.” Sima Guang considered this reasonable.

After the Song dynasty, the shenyi was rarely worn except for special occasions. Ming scholar Qiu Jun noted, “According to Ma Duanlin’s research in Wenxian Tongkao, shenyi was already rare in Song attire, let alone several centuries later.” By the 17th century, Ming scholar Zhu Shunshui, when asked in Japan about shenyi construction, admitted he had never seen one in person. Song-Yuan historian Ma Duanlin, in Wenxian Tongkao, recorded that although attire varied across the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, only the miànfu (ceremonial crown robe) and shenyi were widely worn. The xuanduan was worn by everyone from emperors to scholars, while the shenyi could be worn by all social classes, including commoners, especially by scholars before attaining office. Its extended front panels complied with ritual propriety, so anyone, regardless of rank, could wear it. However, as traditional clothing styles faded, later generations regarded the shenyi as unusual; wearers were often seen as pedantic or outdated scholars. Even Neo-Confucianist Shao Yong expressed reservations, while Sima Guang, Lü Xizhe, and Zhu Xi wore it only privately.

Yuan Dynasty

During the Yuan dynasty, Han Chinese clothing was also influenced by foreign attire. For example, the yesa coat popular in the Ming dynasty, with its high waistline, was inherited from Yuan clothing styles.

Ming Dynasty

After overthrowing the Yuan dynasty, Emperor Hongwu (Zhu Yuanzhang) decreed that “the clothing and headgear system shall follow the Tang and Song traditions,” establishing round-collared robes and other Tang-Song attire as the orthodox dress. He issued a series of edicts that formalized Ming clothing regulations in terms of materials, styles, dimensions, and colors. The core principle was social distinction: different classes and ranks were permitted only the clothing appropriate to their status; no mixing or usurpation was allowed. Violations of these rules were met with immediate and severe punishment. Historical records note, for example, that some commoners were forbidden to wear boots, and thirty-eight residents of Nanjing were exiled for breaking this law.

Men’s clothing in the Ming dynasty largely continued the cross-collared right-over-left robes and round-collared robes of earlier traditions, while also incorporating elements from Yuan dynasty clothing, giving rise to distinctive garments such as the yesa coat. Women’s attire mainly consisted of aoqun (jacket and skirt) or shanqun (tunic and skirt), retaining traditional forms: a single layer indicated a tunic, while double layers indicated a jacket. Unlike earlier periods, the upper garment was no longer tucked into the skirt.

In addition to the enduring tunics, jackets, and skirts, new styles such as xiapei (long ceremonial scarves), beizi, and bijia (vest-like garments) became popular, reflecting a peak in both variety and craftsmanship. The Ming dynasty also saw the introduction of visible buttons in some casual and military clothing, though ceremonial and official robes continued to employ cross-collars and round collars, without prominently displaying buttons.

Ming Dynasty

After the large-scale northward migration of various northern peoples during the Jin and Yuan periods, the clothing situation in the Ming dynasty had diverged significantly from that of the Tang and Song. Although the Ming government repeatedly reinforced bans on “Hu-style” clothing, the influence of Mongol and Yuan fashions persisted throughout the dynasty, particularly in the northern regions. Late Ming writer Wang Tonggui noted: “It is often seen that north of the river, hats still have deep brims, clothing retains waist pleats, and women wear narrow-sleeved short jackets… habits persist and are hard to change, simple and overlooked.”

One notable example is the yesa coat, originally popular during the Yuan dynasty, which from the early to mid-Ming period became the leisure attire of the upper social strata. Emperors, crown princes, inner court officials, and civil servants all wore this coat. Historical records describe Emperor Xianzong strolling in the rear garden in a “bright red dragon-patterned silk yesa”, while Emperor Xiaozong reportedly wore a ceremonial crown and embroidered round-collared robe in the morning, and after meals would don the yesa coat with a jade hook sash, indicating that the yesa was favored for casual or private wear.

Qing Dynasty

In 1644, the Qing army entered China and implemented the queue order and clothing reforms, requiring conquered or surrendered Han Chinese to shave the front of their heads and adopt Manchu-style clothing. This led to the gradual disappearance of Ming official attire in Qing society. However, children, monks, Daoists, and women were still allowed to wear Ming-style clothing. The queue and clothing reforms were difficult to enforce, and many rural Han Chinese continued to dress according to Ming customs. In Jiangnan during the Kangxi era, many commoners still wore Ming-style clothing, and in some regions even into the Xinhai Revolution, Ming styles persisted.

To preserve clothing and hair traditions, Confucius’ descendants petitioned regent Dorgon to protect the attire of the Kong family. Zheng Chenggong’s son, Zheng Jing, used the inheritance of Ming culture as a rallying cry and cited refusal to adopt the queue and Manchu dress as a reason for resistance. Qing emperors recognized the symbolic importance of court attire. They organized officials to study historical precedents, warning against adopting “Han vulgarities.” The Manchu-style court dress combined ethnic characteristics with practicality for horse archery, featuring a bamboo-structured hat, long-beaded tassels, and a waist belt for a sword and fire-striker, reflecting a multiethnic governance style.

A folk saying during the Qing era, “ten obey, ten disobey,” illustrates exceptions to the clothing reforms: men wore Qing attire in life but Ming attire in death, while women and children could retain their previous hairstyles and clothing. Despite strict enforcement, rural areas often maintained Ming-style clothing. For example, the Gengzhi Tu (Farming and Weaving Illustrations) by Jiao Bingzhen during the Kangxi period depicts villagers in Ming-style attire and hairstyles, which the emperor personally reviewed and endorsed. Scholars also note that most non-official Han people were allowed to wear pre-Qing attire, though by the late Qing, most Han voluntarily adopted Manchu-style dress.

Modern Era

In modern China, basic popular clothing includes the Zhongshan suit, Tang suit, and qipao. The qipao, a traditional women’s dress, originated as a school uniform for girls in Shanghai during the early Republic of China and became a symbol of educated modern women, spreading across urban China and Hong Kong. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the qipao was banned for being associated with bourgeois values, but it regained popularity during the 1980s reform era. The Zhongshan suit became a staple for men, particularly government officials and technical professionals. The Tang suit, or Han-style jacket, evolved from Ming-style cross-collared garments and Qing magua, tracing its roots back to the Han and Wei periods.

Since 2002, the Hanfu movement has emerged in China, primarily led by urban Han youth using the internet as a platform. It seeks to revive traditional Han clothing and culture, establishing Hanfu as a social and cultural symbol of ethnic identity.

Costumes in Performing Arts

Dance Costumes

Dance played a key role in Confucian rituals and court ceremonies. The Sanfu Huangtu, Volume Five, records: “During Emperor Wu of Han’s sacrifice to Taiyi, 300 eight-year-old boys and girls danced atop Tian Tai, calling upon the spirits.” In the Tang dynasty, dances were classified into martial (jianwu) and civil (ruanwu) styles. Martial dances were vigorous and powerful, often performed in short-sleeved costumes for ease of movement, while civil dances emphasized grace and flow, performed in long-sleeved garments to showcase elegance.

In formal temple music, instruments such as the bianzhong had delicate, refined tones passed down orally by court musicians. Folk dances, meanwhile, incorporated daily attire or festive garments of commoners and scholars, often with decorative embellishments.

Dance Costumes

Costumes worn during dances are often more decorative than everyday clothing. They typically feature longer sleeves, which help performers express a variety of movements and postures gracefully.

Opera Costumes

Traditional Chinese opera costumes are even more ornamental than regular clothing. While they are not direct replicas of historical or everyday attire, the colors, patterns, and ways of wearing them are carefully designed to indicate a character’s social rank and status, as well as to comply with certain prohibitions against “overstepping” social norms.

Opera costumes can be broadly categorized into five main types: xiaosheng zhezi (young male), peifeng (decorative robes), laosheng mangpao (elder male with dragon robe), guansheng guanyi (official male), and wusheng kaoyi (martial male). After the early Song dynasty, black and white were generally worn by commoners. On stage, the colors yellow, purple, vermilion (red), green, and blue were used in hierarchical order to indicate social rank. This system was not arbitrary; it reflected real-life conventions. “High colors” were reserved for noble and virtuous characters, while “low colors” were used for lowly or villainous roles, illustrating traditional Chinese color symbolism.

Religious Attire

Daoism, a native Chinese religion, has its own distinctive clothing traditions. Daoist priests typically wear plain, unpatterned garments in daily life. During rituals, they don elaborate ceremonial robes and specialized headgear such as the Hunyuan jin, Chunyang jin, and Wulao guan, coordinated according to the needs of the ceremony. Daoist ceremonial robes often feature religious symbols, such as Taiji (Yin-Yang) diagrams or Bagua (Eight Trigrams). The term daopao (Daoist robe) is believed to derive from the Confucian-style robes described in the Zhuangzi. In some Daoist sects, ritual robes became increasingly theatrical, sometimes adorned with water sleeves for ceremonial or performance purposes.

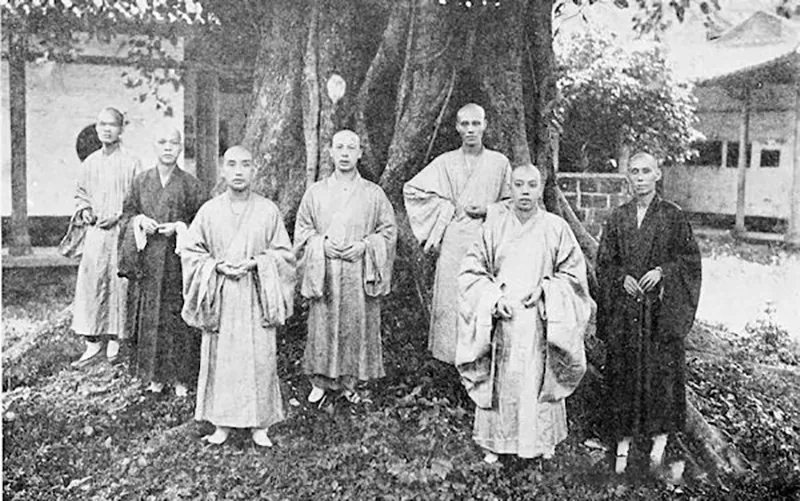

Han Chinese Buddhist Attire

Buddhism originated in India and, upon its introduction to China, became Han Chinese Buddhism. Early monastic attire retained the Indian style, with monks draping the sanghati over their bodies. By the Later Wei period, the robes were modified to include a right sleeve and stitched sides, forming what became known as the pianshan (偏衫, “side-stitched robe”).

Formal ritual robes continued to follow the traditional Indian monastic style, while daily monastic clothing gradually adapted to Han Chinese clothing conventions. Adjustments were made in terms of cut, color, and styling, resulting in a standardized daily robe. By the Ming dynasty, this everyday attire was referred to as the zhiduo (直裰), reflecting a fusion of Buddhist and Han Chinese sartorial traditions.

Attire of Deities, Immortals, and Buddhas

After the Qing dynasty implemented the policy of shaving heads and changing clothing, the traditional attire of deities, immortals, and Buddhas depicted in statues and paintings largely retained the typical Han Chinese clothing characteristics. Although later representations sometimes incorporated theatricalized elements, they still maintained the dignity and ceremonial style of Han officials.

Except for certain figures who emerged during the Qing and were regarded as objects of worship, traditional deities—whether from Han Chinese Buddhism, Daoism, or folk religion—were depicted wearing Han-style garments. Even figures who were originally non-Han, once revered as deities by Han communities, were portrayed in Han clothing. For example, after Buddhism was introduced from India, statues of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas, originally depicted in Indian attire, were adapted to Han Chinese clothing styles in Han regions. Guan Yin Bodhisattva, once considered male in India, was transformed in China into a female figure dressed in ruqun (a traditional Han skirt-and-top ensemble).

Similarly, in Taiwanese folk religion, the Western figure known as the “Eight Treasures Princess” (a European woman who perished in a shipwreck and was killed by indigenous people in Taiwan) is venerated with a statue dressed in Han clothing, rather than the Western-style garments she wore in life.

In Painting

Traditional Chinese painting has often focused on human figures as its primary subject. The earliest surviving Warring States silk paintings already depict Han-style clothing with wide sleeves and narrow waists, reflecting the aesthetic ideals of that era. Stone carvings from the Han dynasty and figure paintings from the Tang and Song dynasties similarly emphasize the clothing styles of their respective periods.

Tang dynasty masterpieces such as Grinding Hemp (Daolian Tu), Palace Music (Gong Yue Tu), and Ladies Adorning Hair with Flowers (Zan Hua Shi Nu Tu) represent the pinnacle of Chinese court lady painting and serve as important references for the study of historical Han clothing. Likewise, Ming dynasty realist paintings, including genre scenes and portraiture, also faithfully record the clothing styles of their time.

Painter Fang Rending noted that during the Qing dynasty, “Han clothing was forbidden, and the attire of non-Han peoples was used by unscrupulous painters in their works.” However, surviving artifacts show that Chinese figure paintings from the Qing period to the present depict people wearing both Qing-style clothing and Ming-style attire.

Influence on Other Ethnicities’ Clothing

Han Chinese clothing culture significantly influenced neighboring peoples and other Confucian cultural states. The Hua Xia court etiquette also stipulated that rulers of the “Four Barbarians” must wear their own national dress when paying tribute to the Chinese emperor, a practice called “foreign rulers wearing their own attire.”

During the Han and Tang dynasties, China implemented a tributary system in which neighboring ethnic leaders were required to pay regular visits to the emperor, known as the chaoji (朝集) system. Under this system, whether foreign monarchs and their envoys came to the Chinese court to offer tribute and receive official titles, or the Chinese emperor hosted foreign rulers, these rulers were required to wear their own national dress as a sign of respect and adherence to Chinese ritual protocol.

In the early Ming dynasty, a series of clothing prohibitions were indeed implemented, including bans on civilians wearing duijin robes (overlapping front jackets) and zhao jia (armor-like outer garments). These regulations were primarily aimed at maintaining social order and the hierarchy, using strict clothing rules to distinguish the identity and status of different social classes. However, over time, these bans gradually relaxed, and garments such as duijin robes and zhao jia eventually became popular among the general populace.

Regarding the origin of the magua (riding jacket), some scholars, such as Ding Chao, have proposed that it may have originated from the Ming dynasty’s duijin robes. However, other scholars, including Liang Qichao and Zhang Taiyan, disagree, arguing that the magua has no direct connection to Ming clothing. This scholarly debate reflects the diversity and complexity inherent in historical research.

During the Tang dynasty, the Dunhuang region was occupied by the Tubo (Tibetan) forces, and the local Han Chinese were compelled to adopt Tubo customs, including dress. Yet, on certain occasions, such as ancestor worship, they still wore Han clothing to express loyalty to their homeland and adherence to their ethnic traditions. This behavior demonstrates the Tubo Han’s efforts to preserve their cultural identity and highlights their ongoing connection with the Tang dynasty.

By the Jin dynasty, the government issued decrees prohibiting civilians from wearing Han clothing and enforced hair-cutting policies to strengthen ethnic control and assimilation. Eventually, under the reign of King Hailing, these restrictions were relaxed, allowing the people of Henan to freely choose their attire. This loosening of policy led to the Sinicization of Jurchen clothing, illustrating the unstoppable momentum of cultural integration.

The Ming dynasty’s policies toward the Duzhang people represented a form of cultural assimilation, aiming to weaken their cultural distinctiveness and identity through forced name changes and clothing reforms. Such practices were not uncommon in history and were typically employed to consolidate new regimes or suppress resistance among conquered groups. The elimination of the Duzhang’s cultural markers reflects the Ming dynasty’s approach to controlling and assimilating border regions.

During the period when Annam (Vietnam) was under Ming control, the Vietnamese were also compelled to adopt Ming culture and attire, primarily through the policy of “hair binding and clothing change” (shufa yifu). Ming officials viewed this as a way to “civilize the barbarians,” enforcing bans on cutting hair and mandating the wearing of Han-style clothing to strengthen central authority and unify cultural standards.

Traditional clothing in neighboring countries, such as Japan’s kimono, Korea’s hanbok, Vietnam’s four-piece ao, and Ryukyu’s ryuso, were all influenced by the clothing system of China’s Central Plains dynasties and Han Chinese attire. This influence often occurred through cultural exchange, trade, or even direct governance and conquest. For example, while Japan was influenced by Chinese culture, it developed its own distinct traditional attire—the kimono.

In early 18th-century Europe, there was a brief fashion trend known as “Chinoiserie,” reflecting European fascination with Chinese-style clothing and decorative elements. This trend illustrates cross-cultural exchange driven by curiosity and admiration for foreign cultures, demonstrating how interest in exotic customs can inspire imitation and adaptation across cultural boundaries.

The legacy of Chinese clothing tells a story of culture, artistry, and social tradition spanning thousands of years. From elegant Hanfu to intricate Tang suits, each piece carries historical significance and aesthetic beauty.

Explore our Hanfu Collection, and bring the elegance of ancient China into your modern wardrobe.